A Green Deal must include a Care Deal – Maternal mental health under the spotlight at EU Parliament

23.11.23

On November 7th, we co-hosted an event at the EU Parliament on peripartum depression with MEP Maria Noichl.

We heard from numerous speakers from diverse backgrounds on the importance of supporting women who have symptoms of depression before, during, and after pregnancy. Despite knowing that the negative effects of poor maternal health are many, for both mom and baby, there are no EU-level policies right now that specifically address this.

That being said, at the event, the RiseUp-PPD project, of which Make Mothers Matter (MMM) is a partner, presented its newly published evidence-based clinical guidelines on screening for and treating peripartum depression (PPD) across Europe. These are the first of its kind – a big win for women’s health. RiseUp-PPD stands for the Research Network in Peripartum Depression Disorder and is a COST (Cooperation in Science & Technology) Programme-funded network of researchers and professionals that aims to fill gaps in PPD research and increase social awareness.

- MEP Maria Noichl (S&P) set the tone with her welcome words. She has been a German Member of the European Parliament since 2014 and is also an active and committed member of the Parliament’s Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, which advocates for women’s rights in general. A mother herself, Maria stressed the urgent need for a Green Deal that also includes a Care Deal, with a particular focus on women’s mental health and wellbeing before, during, and after pregnancy. She added that organizations like MMM play a very important role in advocating for and bringing this topic to the attention of policymakers and advocating on behalf of this. Maria said, “This is some of the most important work that we can and have to do together.”

- Professor Ana Ganho Ávila, a clinical psychologist at the University of Coimbra, Portugal and action chair of the RiseUp-PPD project, introduced the project and the group’s newly published guidelines. The guidelines are mainly geared toward clinical practitioners to help them screen for and treat PPD in practice, as well as to try to prevent it in the first place by better-supporting mothers during what is a time of great change and increased vulnerability. In fact, pregnancy is reportedly the time when most women come in contact with the healthcare system, regardless of their background or access to resources; therefore, it is a great opportunity to intervene in both their physical and mental health. Prevention is not only the job of clinical practitioners though, but a collective responsibility for all of us to take part in and promote in our communities. The most important thing, Professor Ganho Ávila says, is to be willing to have open and honest conversations about mental health and of course to be compassionate towards each other. The guidelines can also be used as a resource for new mothers and their families to know what “warning signs” to look out for in themselves and others.

Relatedly, MMM recently sat down to speak with Professor Ganho Ávila about the urgent need to break the silence on maternal mental health and the role we all play in achieving that. Listen to the conversations here. - Professor Mariana Moura Ramos also works at the University of Coimbra, Portugal as a clinical psychologist. Professor Sandra Nakić is a psychologist from the Catholic University of Croatia and is vice-chair of RiseUp-PPD. Together, Professors Ramos and Nakić explained more about the clinical guidelines and how their wish is for all clinicians who work with mothers and their families to become familiar with them, and hopefully adopt them in their daily practice. They firmly called on the MEPs in attendance to support the guidelines and to circulate them in their circles of influence, establishing them as the go-to reference for engaging in maternal mental health work.

- Lena Yri Engelsen is the Secretary General of the Norwegian-based patient organization 1001 Days. Their objective is to support positive maternal mental health and subsequently healthy emotional development in the infant during the first 1,001 days. The idea behind this is that the first 1,001 days are known to be a period of increased infant sensitivity to the environment, particularly the attentiveness of the primary caregiver (in most cultures, this is the mother). We know that when mothers suffer, their babies suffer, too. Lena also highlighted the fact that pregnant women and new mothers are not often formally recognized as vulnerable groups in society and that we have to push to change this so they are more protected within our health, social, and legal systems.

In addition to telling us about their seminal work in the Nordic countries, Lena also contributed meaningfully to the conversation as a patient advocate herself, talking about her own birth experience and what she has heard from other mothers. This is a critical piece of advocacy work – hearing directly from those who have experienced the phenomena and can share their insights. One of Lena’s main takeaway messages was that, “You are not a bad mother. There is nothing wrong with you. With the right help, you will get better.” Through the work of the 1001 Days project, her hope, as it is ours, is to one day close the health gap (in maternal mental health) that affects so many new mothers and to make access to care more accessible, of higher quality, and more patient-centered. She added that “if we don’t plan, we plan to fail the next generation.” - Professor Annette Bauer, an Assistant Professor and Research Fellow in the Care Policy and Evaluation Centre at the London School of Economics, told us how poor maternal mental health is strongly influenced by various social determinants, such as gender discrimination, violence, lack of social support, socioeconomic status/poverty, substance abuse, and natural disasters, among others. We should be attempting to address these underlying causes as well, for the betterment of society as a whole. Professor Bauer, an economist, also presented some startling figures about the economic impacts of the situation in Europe. After seeing these, we should all be driven to make change happen – now. Professor Bauer, for example, highlighted that, if left untreated, the estimated cost burden for the EU will be upwards of 8.1 billion euros; ⅔ of this comes specifically from the long-term impact of how a mother’s mental health can affect that of her child(ren). According to Professor Bauer, we know from cases in other countries (e.g., the UK, South Africa, France, Canada, Italy, Spain) what would likely work plus be cost-effective; however, in most of Europe, we are not putting this knowledge to good use. Professor Bauer insisted that the EU has the ability to be a lead change-maker in this area – to put our mothers and children at the forefront. What is needed is greater political support and more resource allocation.

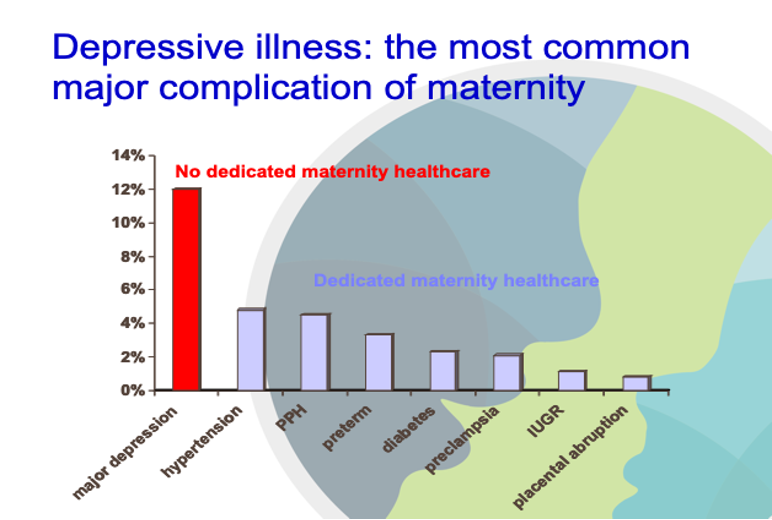

- Dr. Alain Gregoire is a consultant perinatal (mother and baby) psychiatrist in the UK. He was the founder and is current Chair of the Global Alliance for Maternal Mental Health and founder and President of the UK Maternal Mental Health Alliance. Dr. Gregoire powerfully framed maternal mental health as a society-wide “hidden pandemic” in his passionate call to action. According to Dr. Gregoire’s reports, depression is the number one major complication of maternity. The pregnancy and postpartum periods are the highest risk one will ever be at for severe mental illness in our lives. In many places (even in developed places like the EU!), it is the leading cause of maternal death. The effects of this also extend to the infant/developing child. For example, if a mother has anxiety during her pregnancy, this doubles the risk of the child having emotional and behavioural problems later on. In one study Dr. Gregorie presented (Pawlby et al., 2009), it was found that adolescents who had depression at age 16 all had mothers who reported being depressed during or after their pregnancy. For the cohort of mothers who did not report depression, none of their teens did either. In other words, we know that early emotional adversity and poor mental health are trans-generational. One interesting thing that Dr. Gregoire asserts is that for children living in poverty, it is not the subpar conditions themselves that have the greatest negative impact. Instead, it is the mother’s emotions and internalization of poverty that gets passed on, whether that be as early as in the womb or as the child develops. Watch the conversation series we had with Dr Gregoire on Maternal Mental health here

Despite these gloomy facts, Dr. Gregoire brought everything together by assuring us that there is hope. This “hidden pandemic” can be avoided with the right action taken. As members of civil society, we all have the responsibility to speak up and demand action be taken and sustainable change made. To ensure that all women, regardless of varying social determinants of health, will have easy access to high-quality, patient-centered maternal care in Europe, Dr. Gregoire made the following five recommendations:

- Have specialists in perinatal care (including before, during, and up to 2 years after pregnancy)

- Training for all care providers, regardless of speciality

- Communication and coordination between all staff and services

- Appropriate allocation of resources, including financial (here is where political actors can have the biggest impact)

- Europe-wide action on greater awareness of maternal mental health and an effort to decrease stigma

To complement these, you can find MMM’s call to action on maternal mental health here.

In the closing remarks, MEPs Maria Noichl and Radka Maxova (S&P) stressed the urgent need to recognize and include mental health during the peripartum period, and that this should be formalized in laws and policies. Since women constitute more than 51,7 % of the European population, their health – both physical and mental – should matter to Europe and its key decision-makers.

MMM’s President, Anne-Claire de Liedekerke, summed up the event’s objectives by saying: “Working together with researchers, policymakers, and civil society is necessary. These findings can then lead to policy-making, awareness raising, and bringing about change in the lives of mothers and their families.” After all, happier and healthier mothers means happier and healthier children and by extension, communities at large.

MMM wishes to sincerely thank all our speakers and those who attended the event. A special thanks to MEP Maria Noichl for opening the doors of the EU Parliament to discuss maternal mental health.

Breaking the Cycle: Gender Equality as a Path to Better Mental Health

18.03.25

The Council of the European Union has taken a decisive step in recognising the vital connection between gender equality and mental health.

Europe Must Listen to Mothers: Our landmark report heads to the European Parliament

28.08.25

On 22 September 2025, the voices of mothers will take centre stage in Brussels. For the first time, Make Mothers Matter (MMM) will present its State of Motherhood in Europe

Ensuring Work-Life Balance: The EU’s Commitment to Supporting Parents, notably mothers, and Gender Equality

19.03.25

At the latest EPSCO Council (Employment, Social Policy, Health, and Consumer Affairs), the Council of the European Union adopted groundbreaking Conclusions aimed at addressing work-life balance and pr